As some of you know, I will soon fulfil my (not quite lifelong but certainly since I was 19) ambition to become a teacher when I return from Zambia; the Olympics and Paralympics just got in the way really! In fact, this ambition was one of the reasons that I have chosen to spend two months here in Lusaka as I wanted to see some teaching and coaching of children in a different setting to the myriad schools that I have attended, visited or taught at previously, predominantly in the UK. To say I underestimated how big the differences might be, both good and bad, would be a ludicrous understatement.

The first weeks of my work here have been rather dominated by the corporate relations work that I have been doing but, having realised that the end of my visit is fast approaching, I resolved to make more effort to get into some different schools. And not only did I just want to visit; I wanted to teach and coach too. This week, I have taught twice at a school called Fountain of Hope (see a previous blog) to a grade 1 class and a grade 5 class, observed football coaching at Munali and visited the University Training Hospital Special School to take part in fun and movement games.

As some of you will heave heard before, I have always been confused by the different naming systems in UK schools for the pupil year of study (e.g. Year 7, Lower Sixth, Reception, Removed, Shell) and have previously proposed that we just change every school (independent and state) to have a system where the Year is the same as the age of the pupils (i.e. Year 13 for thirteen year olds). Not only would this avoid confusion, it would also remove the social stigma immediately attached to anyone revealing they were part of a different system; enforce it in state schools and make it obligatory for charitable status in independent schools.

This system would not work in Zambia though. Owing primarily to the range of circumstances which first lead someone to be willing, able and fortunate enough to be able to attend school, there is a significant range of ages attending each grade. This was somewhat apparent in the grade 5 class yesterday, where my previously unrecognised fashion talents were tested to the limit in a class about textiles and fabrics. However, the grade 1 class, where I was more at home discussing shapes and numbers, had pupils ranging from 7-14 years old (by my estimate) all learning together. The pupils seem, perhaps because this is near the end of the academic term, to take this in their stride but for the teacher, a British one at least, where the current trend is of course to celebrate diversity in all its shapes and forms, this could exacerbate what must already be a tricky emotional situation for the older pupils. I hope I got the balance right.

Whilst this is a tricky difference to manage, I said there were some positive differences in the schools I have visited here too. For instance, a proportion of the children have chosen to attend school; there is no obligation to attend for those who cannot afford it or who have been raised in circumstances beyond my previous comprehension. This means that these children are mature beyond their years (I suspect sometimes having also lost their innocence tragically), eager to learn and keen for structure and discipline to be maintained in class, as much as any child really craves these pillars of education at least. Whilst I am not sure I would claim to have had full control or undivided attention in my classes, I suspect the level of unruliness would have been much worse in a class of 45 British pupils.

Other positives include the ability to play not being affected by the seeming lack of resources (witness the football match played with an empty plastic bag) and the immediate friendliness of the pupils, especially the case at the Special School (their name, not mine); I lose count of how many times children approach me asking, “How are you?”, a common phrase they learn to say, never seeming entirely interested in (or even aware there should be) an answer. And you also have to be ready for the fist bumps, high fives and, of course, the handshakes, Zambian style (which I suspect I might unwittingly employ in the UK when I get back).

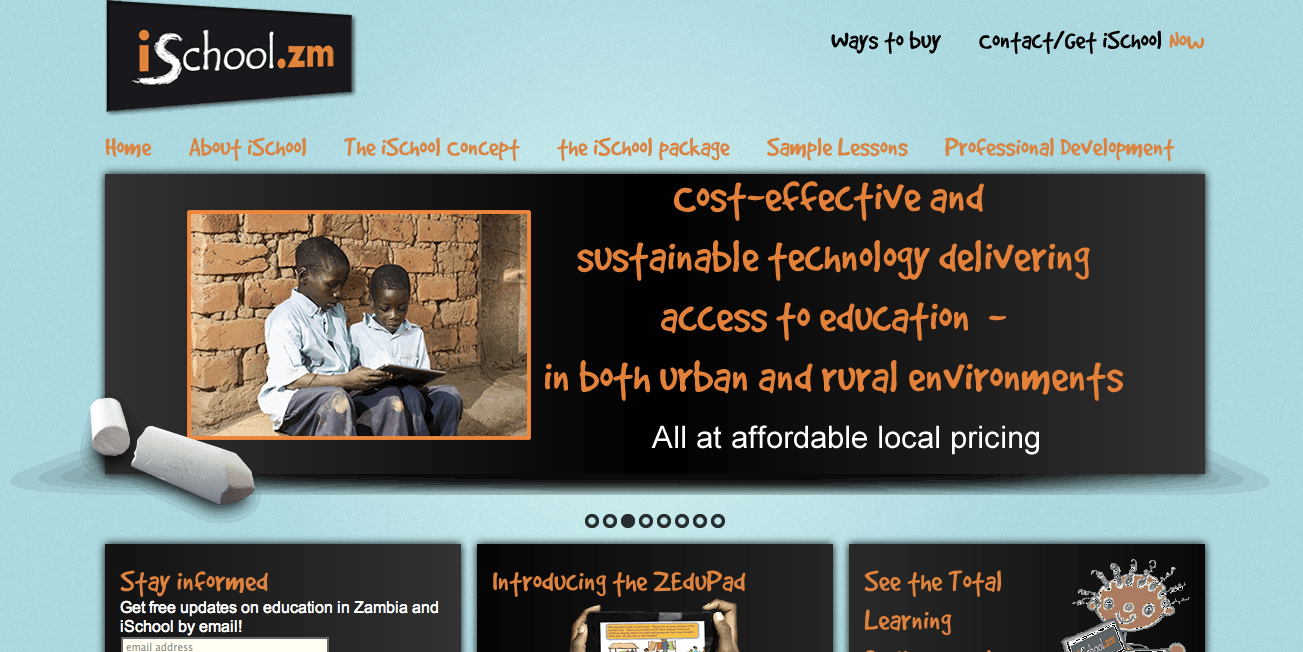

That said, the educational challenges here are huge. Over seven million potential pupils under the age of 15; some schools with no classrooms and few books; children still required to earn money for the family in order to survive, at the expense of their education and future. Which brings me on to easily the most exciting meeting that I have had here with a company called iSchool. Mark Bennett has led a team there firstly to capture the entire Zambian school curriculum electronically, including translations into the eight local dialects and English as well as picture storyboards for those not yet able to read, and then to provide this via both bespoke electronic devices and the web.

The potential for this I believe is huge. Containing both lesson plans for teachers as well as lessons for pupils, Mark and his team have of course had to take all manner of local considerations into account: how to charge the device when power can be hard to come by; what local customs will pupils be able to understand (e.g. to explain trade, use the roadside market); and what experiments will pupils be able to carry out (e.g. to explain heat, use a fire). For those of you interested in education, those of you looking for an investment opportunity or those of you interested in Zambia, I would highly recommend having a look at the website and finding out more. Today Zambia, tomorrow, Africa?

In the meantime, I am hoping that I can find some ways for Sport in Action and iSchool to work together as the synergies are fairly obvious and I hope we can help him spread the message and the opportunity. That, after all, is all education really is.

Posted in 2013